The Future is ... Pagan?

A review of the Edinburgh Art Festival 2025

"Fair is foul, and foul is fair" Macbeth, William Shakespeare

The world is out of joint. Distracted by smartphones, with microplastics accumulating in the brain, haunted by demonic AI and malevolent algorithms, it’s all leading to a fraying social contract and violence in the streets. The world seems to be heading in the wrong direction. Is it any wonder that people might turn to the old gods?

While there is no one overarching, all-encompassing theme in this year's Edinburgh Art Festival (EAF), the curators note some "recurring motifs" including "classical myths, folklore, modern feminist empowerment, queerness through the lens of Scottish history". The festival's director, Kim McAleese, invites audiences to "reflect on our collective relationship with the natural world" and draw inspiration from how "ancestral knowledge can guide us in addressing contemporary challenges".

Now, the human brain is primed for pattern recognition. We can take any number of random inputs and, with enough ingenuity, turn them into a word or phrase. Many art festivals and biennials1 employ catch-all terms like Foreigners Everywhere, Bedrock, and Intelligens as a hook to hang expectations. What can we do with EAF? What sprang to my mind was Paganism. Myths, folklore, nature … it's all pagan, no?

The trouble with the word pagan—which derives from the Latin word meaning rustic—is that it’s the enemy’s description. That is, it is a term used by an urban elite to dismiss humanity’s messy and diverse beliefs.

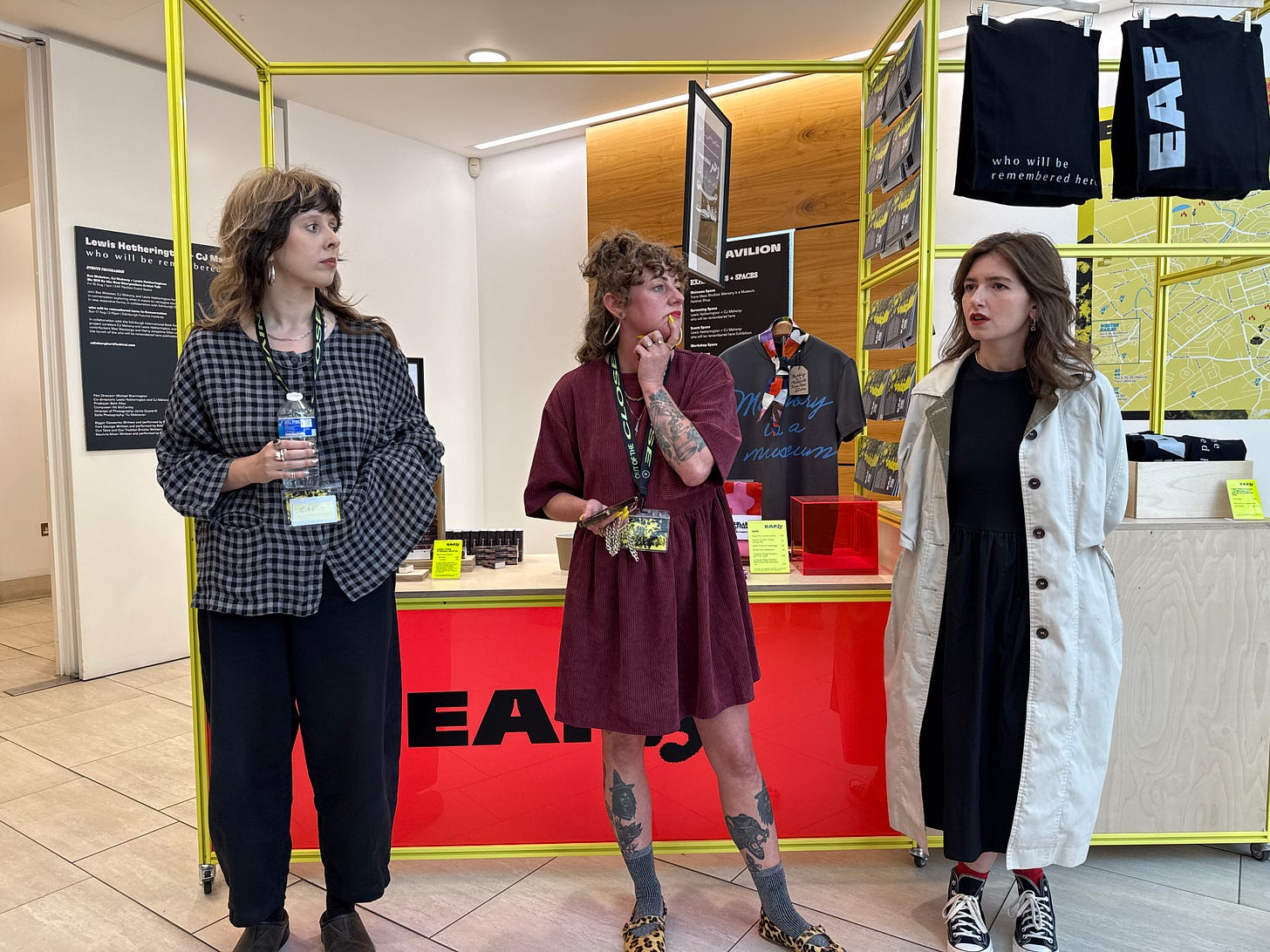

Nevertheless, a pagan tone is set with the centrepiece of the EAF Pavilion: Lewis Hetherington and CJ Mahony’s "who will be remembered here", an emotionally charged film about the suppression of marginalised identities and languages across Scottish history. It features monologues from a gay man with Cerebral Palsy, a Gael poet, a trans woman, and a deaf non-binary Thai Scot, all of whom rail against an establishment that had silenced them in the past. It's an impressive, moving work, albeit one that is filmed with the slickness of a car commercial.2 By combining the four stories across time, the filmmakers create a coalition of the marginalised. It’s as if to say: we may be separated by language and culture, but we are united in our oppression by the imperium.

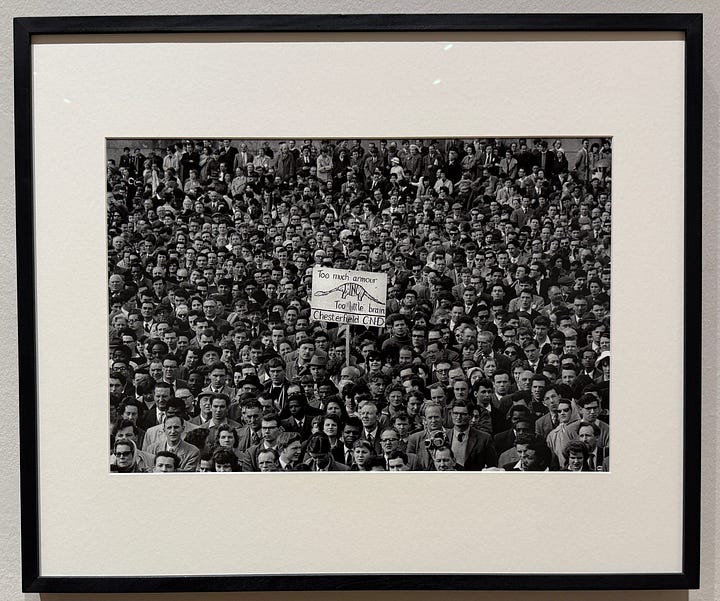

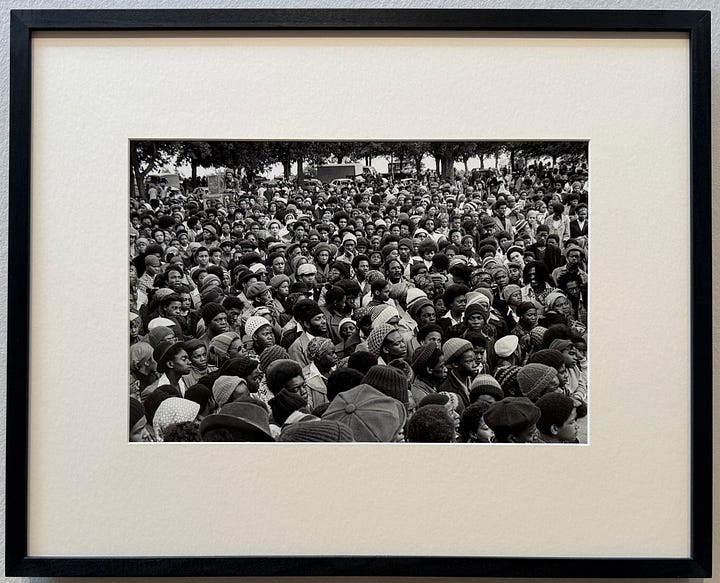

A similar premise is at play in the exhibition of protest photography at National Galleries Scotland: Modern Two. Resistance, curated by Sir Steve McQueen CBE, shows how different groups—from the suffragettes to poll tax rioters—helped bring social justice to the UK and stymied the slide into fascism. It's all very honourable, but the presentation tends to flatten the social history. Every photograph is black and white and displayed in the same way. The individual struggles blend into one, and start to resemble what has been derisively called the Omnicause.

While the photography is often thrilling—I particularly enjoyed seeing work by Philip Jones Griffiths and Vanley Burke—the exhibition never connects with modern resistance. Everything feels historicised and done.

By contrast, Humpty Dumpty, Mike Nelson's takeover of Fruitmarket Gallery, rubs our faces in the entropy of our present, showing that all that's left of the old ways is wreckage. Nelson's jerry-built frames, rescued from a building site, contain photos of social housing before it was transformed into luxury apartments. In the warehouse next door, he built a disturbing, immersive recreation of those derelict flats.

According to the bookseller at Fruitmarket, Nelson learnt everything he knows about sculpture from the Strugatsky Brothers’ Roadside Picnic (itself the basis for Andrey Tarkovsky's Stalker). In both cases, we are in a world of ruins, of pessimism and futility. No wonder people might want to escape into new belief systems.

I've written previously about how some form of nature religion seems inevitable in the age of climate change. A few artists have been tentatively reaching similar conclusions.

At Stills, Siân Davey invites us into The Garden, a wildflower paradise she created with her son during lockdown to take portraits of passersby. As a former psychotherapist, Davey uses portrait photography partly to discover and integrate things within herself. And it is a remarkably sensual experience with the luscious bodies standing out against the wildflowers. Since lockdown, the garden has fallen into disrepair. Wildflower gardens are, apparently, not self-sustaining. What we think of as nature only exists with human intervention.

This tension between humanity and nature is the subject of Andy Goldsworthy, who has been honoured with a career retrospective at the National Galleries of Scotland. In Fifty Years, Goldsworthy takes over the Royal Scottish Academy building with stunning installations in wool, oak, stone, and fern. He shows the harsh reality of country life with fences of barbed wire and sheep’s wool.

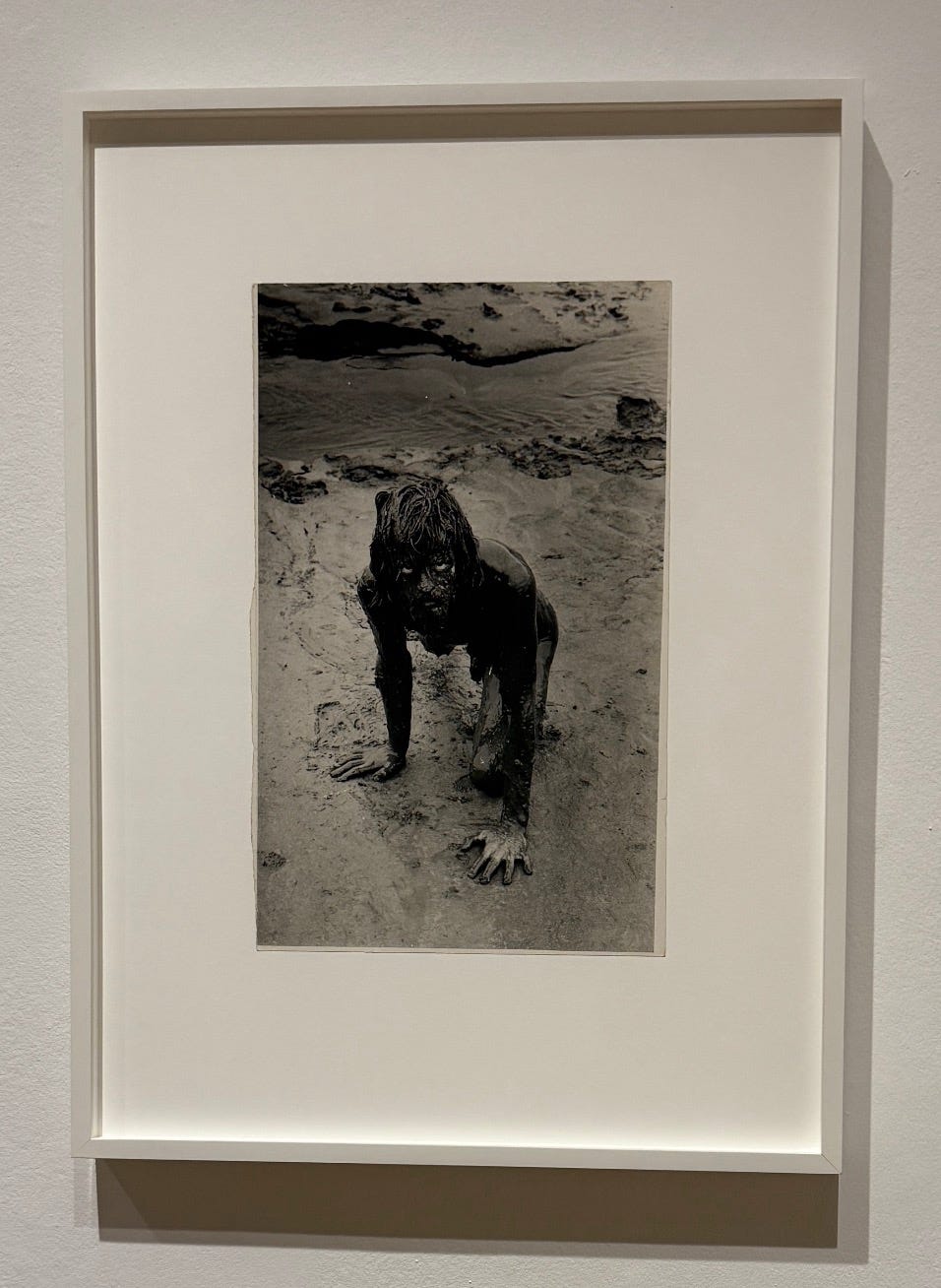

The upper floor, which contains most of the new installations, is breathtaking. It is in his early photography, however, that I found the most joy. Sometimes seen merely as artistic documentation, these are some of the freshest photos I've seen this year. Goldsworthy is covered in mud, throws sticks in the air, and creates delicate arrangements of leaves. Individually modest, as a body of work, it is kaleidoscopic.

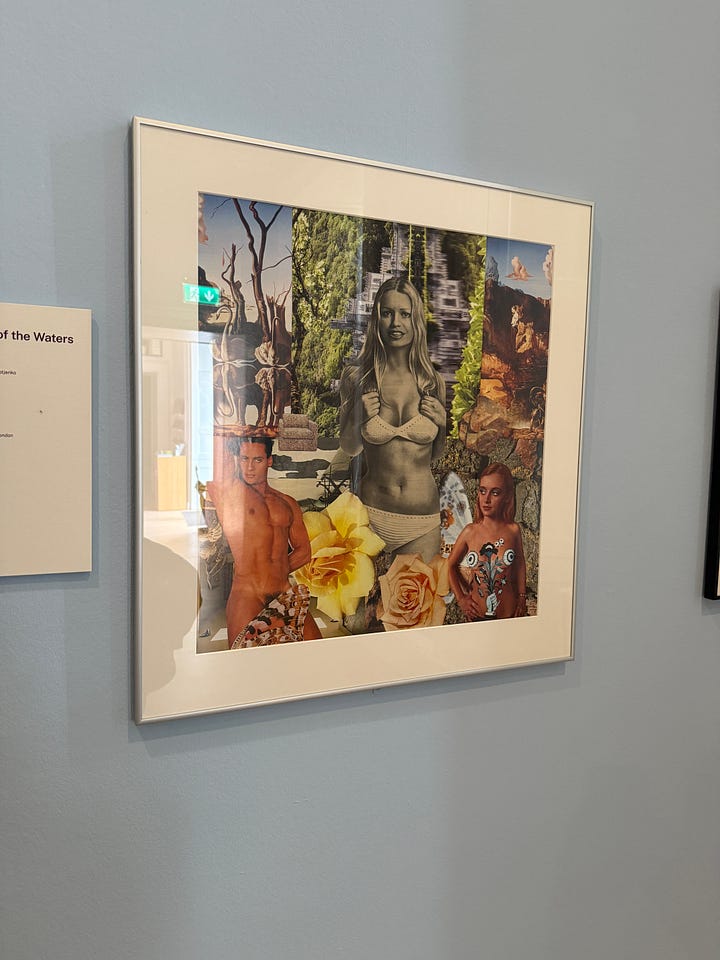

A rather different fifty-year retrospective takes place in the Royal Botanic Gardens. Linder's Danger Came Smiling at Inverleith House is more modest than Goldsworthy's extravaganza, but both exhibitions show how an artist's work accumulates meaning over time.

Linder's early photomontages are stark satires of patriarchal expectations, while her later work seeks meaning in myth and natural forms. For a performance co-commissioned by Mount Stuart Visual Arts, this collapsed into a pagan improvisation where the dancers became enchanted by fallen branches. It’s both visually and mentally stimulating; a heady mix of discomfort and joy.

But what are we to make of all this? At any other time in the last 500 years, the kind of heathenism in EAF would have been met with strident Presbyterian denunciation.3 But the Kirk is so toothless and weary that St Giles’ Cathedral is hosting an event by Raven Chacon, an indigenous artist, critiquing the Church. St Giles’ Cathedral was the very place where John Knox was minister… though he would be cheered to know that it was the Catholic Church that was complicit in the abduction of children in South America.

The split between Protestants and Catholics is central to The World of King James VI & I at the Portrait Gallery. This fierce exhibition tells a story of assassination, paranoia, and violent retribution. It provides a stark reminder of a time when political power was centralised.

During James’s reign, hundreds of women were accused of being witches. Many were executed. At the same time, the East India Company were establishing the template for colonialism. In our more enlightened age, it would be easy to portray James as the villain, but exhibition shows him as a victim of geopolitical circumstances.

It was James I's accession to the throne that led Shakespeare to write Macbeth, that strange play about destiny, which features three witches. I was reminded of this fact during the press launch when listening to the introductions by three curators. Glancing down, I saw two witches and various animals tattooed on the festival director’s legs.

While art helps shape our understanding of the zeitgeist, it has no power over the direction of history. The future is probably not going to be pagan, however the Edinburgh Art Festival is worth visiting to understand what varied forms of resistance are now possible.

The EAF is not a biennial; it runs every year. Its curator, Eleanor Edmondson (good Shakespearean name!), told me at the launch of EAF25 that they had just signed off on next year's programme. It’s also worth noting that, apart from a handful of commissions, the curators have little control over the art on display in the city. Even so, it’s all in one catalogue, inviting us to see the work as a whole.

It was made in collaboration with Historic Environment Scotland, who presumably also want people to visit the sites shown.

The 2022 census shows that 51% of Scots have “no religion” and Church of Scotland affiliation is down to 20%, although regular churchgoing is much smaller. For a fictional portrayal of the state of the Kirk, I recommend Chris Kohler’s Phantom Limb—out now in paperback.

Art by self-absorbed, resentful people who need to cheer up a bit.

I quote Ronald Hutton, The Triumph of the Moon, 2nd ed., p. 4:

"For over a hundred years writers had commonly asserted that the Latin word paganus, from which it was derived, signified 'rustic'; a result of the triumph of Christianity as the dominant, metropolitan, and urban faith, which left the old religions to make a last stand among the more backward populations of the countryside. In 1986, however, the Oxford-based historian Robin Lane Fox reminded colleagues that this usage had never actually been proved and that the term had more probably been employed in a different sense in which it was attested in the Roman world, of a civilian; in this case a person not enrolled in the Christian army of God. A few years later a French academic, Pierre Chuvin, challenged both derivations, arguing that the word pagani was applied to followers of the older religious traditions at a time when the latter still made up the majority of town-dwellers and when its earlier sense, of non-military, had died out. He proposed instead that it simply denoted those who preferred the faith of the pagus, the local unit of government; that is, the rooted or old, religion. His suggestion has so far met with apparent wide acceptance."

If you want to understand the real origins of the association of paganism with the countryside, the folk, and nature - and, indeed, the association of paganism with witchcraft - you can't do better than reading Hutton's book. One of the many exceptionally deep lessons it has to teach is that 'pagan = countryside = non-urban' is _not_ an enemy's description; it was a self-conception right from the start, something that was seized upon by those who wanted to celebrate paganism or even identify as pagan themselves; in many ways the real enemy's description is the idea that Christianity is the religion of the urban elite. (Many revolutionary movements across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have learned the hard way that the peasantry really are _very_ Christian!) The difference was that 'the start' in terms of our contemporary ideas of paganism is not antiquity but rather Romanticism. (Hutton's might be the best book I've ever read about the legacies of Romanticism, even if that's not how he'd sell it.)