One thing I know from living in Scotland all these years is that tall-poppy syndrome is endemic. You learn to be self-deprecating and not get too big for your boots. Glaswegians, in particular, don’t take well to pretension.

So, while I was delighted to see last week’s post about Greenock linked to by The Glasgow Bell, it was slightly unsettling to be labelled as “Glasgow’s premier flâneur”. Had The Bell painted a target on my back?

Fortunately, no one I spoke to had even heard of the word flâneur. It was like being the West End’s pre-eminent wandervogel or Paisley’s number one peripatetic. I had been saved by obscurity.

But it made me pause: am I a flâneur? And, if so, what does that entail? The definition that pops up on Google is: “a man who saunters around observing society.” This sounds about right, although I am usually rushing around rather than sauntering.

A more poetic description of the flâneur can be found in Charles Baudelaire’s essay, The Painter of Modern Life:

For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world [… ] the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy.

Yes! This is the thrill of modernity, of being part of the crowd yet still able to observe patterns amid the chaos.1

In On Photography (1977), Susan Sontag aligns the flâneur with the street photographer, who is:

an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitring, stalking, cruising the urban inferno, the voyeuristic stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes. Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, the flâneur finds the world “picturesque.”

It’s a seductive passage, but one that better fits the decadent excesses of seventies New York than modern Britain.

Last weekend, I was in England visiting family and found myself playing pool in an industrial estate.

Rather than the urban life, I was drawn to take photos of bales of popcorn at the cinema before seeing Hamnet.2

We arranged our train bookings so that we could spend an hour in Birmingham, whose modern towers were shrouded in mist.

The centre of Birmingham has been transformed with flashy new developments.

It seems a shame that almost all the sculptural brutalist buildings and fittings are being replaced by vulgar bling.

Next to the gilded library is a gilded statue of Matthew Boulton, James Watt, and William Murdoch. It’s really vulgar … almost Trumpian.

When in Birmingham, I always take the opportunity to visit The Ikon Gallery, one of the best contemporary art spaces in Britain.

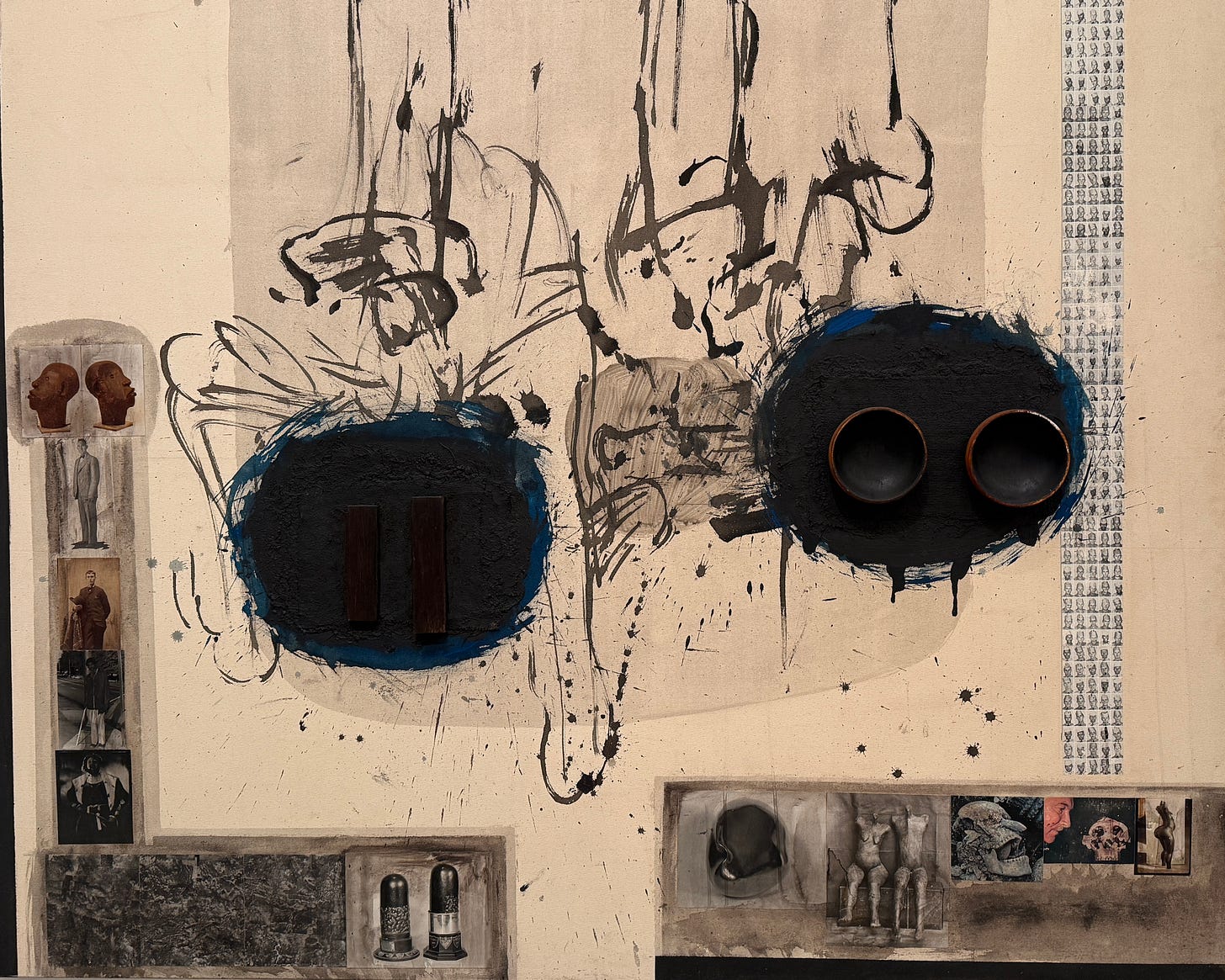

Their current exhibition is a retrospective of Donald Locke (1930-2010), a Guyanese sculptor whose maximalist paintings employ photography in a stark, expressive way.

Locke shows what happens when an artist wrestles with identity in their work. As Eddy Frankel writes:

Amazingly, Locke, who died in 2010, at first rejected any political reading of the works, insisting they were just exercises in form. It wasn’t until years later that he realised how overburdened with the pain of colonialism the works really were.

Part of the reason I resist identity politics is that I find it impossible think of myself in terms of labels. This is the privilege of one who hasn’t had a label assigned to them. However, now that I have been assigned a label—the flâneur—I begin to understand how it could induce self-consciousness.

While on the train down to England, I compiled what will hopefully become the definitive timeline of the controversial artist Sophie Calle:

The subject of Baudelaire’s essay was the painter Constantin Guys, who is described as having an “aim loftier than that of a mere flâneur”:

He is looking for that quality which you must allow me to call ‘modernity’; for I know of no better word to express the idea I have in mind. He makes it his business to extract from fashion whatever element it may contain of poetry within history, to distill the eternal from the transitory.

I enjoyed it, particularly the opportunity to cry in a dark room. For an alternative perspective, check out Heather Parry’s blistering negative review.

I am a big fan of Sophie Calle, so I would like the rest of the calendar. Suite Venitienne is a project I tried to emulate from a different point of view in a photo project a couple of years ago. That aside, I enjoy your blog a lot, and here's an opportunity to say it.

Have you read Benjamin's Arcades? Fantastic exploration of Flaneurism. Would love to hear your thoughts on it. Great post!