Photographing Drug Addiction

Understanding drug addiction through the photography of Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Aidan Mark Wilson

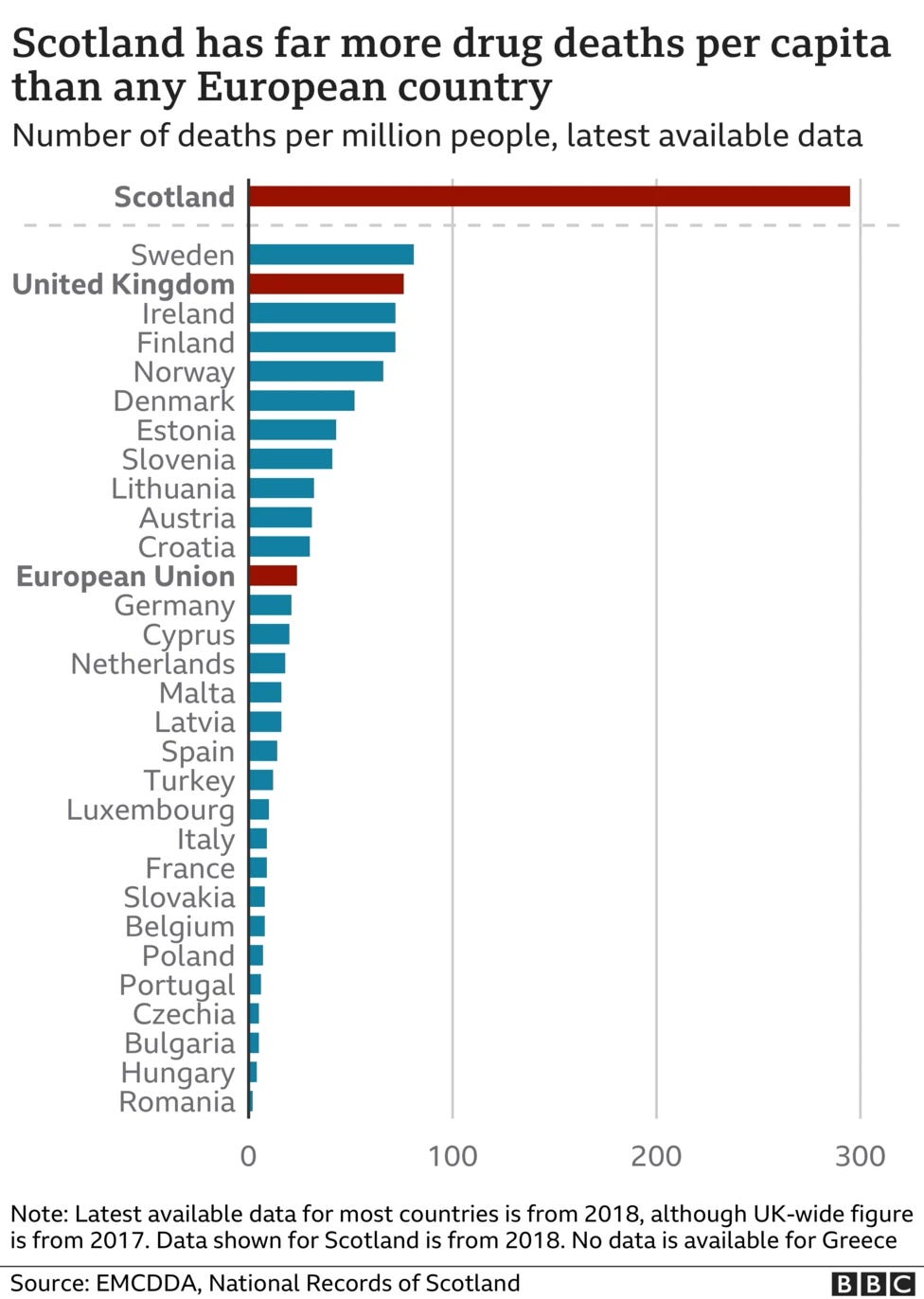

Scotland is the drugs death capital of Europe. In 2024, there were 1,017 drug deaths, which is 191 deaths for every million people. For reference, Estonia has the next highest rate at 135 per million.1 The cry keeps going round: “Something must be done!” But what?

The main response from the Scottish Government has been to distribute more Naloxone, an overdose antidote. They also greenlit an experimental safe consumption centre in Glasgow to give users access to needles and nurses if they need them.2 Mostly, however, addicts are kept in a state of permanent sedation via prescriptions for opiates and painkillers. Compared to methadone, detox and recovery programmes are expensive. Addicts are not deemed a priority because they tend to come from communities that don’t vote.

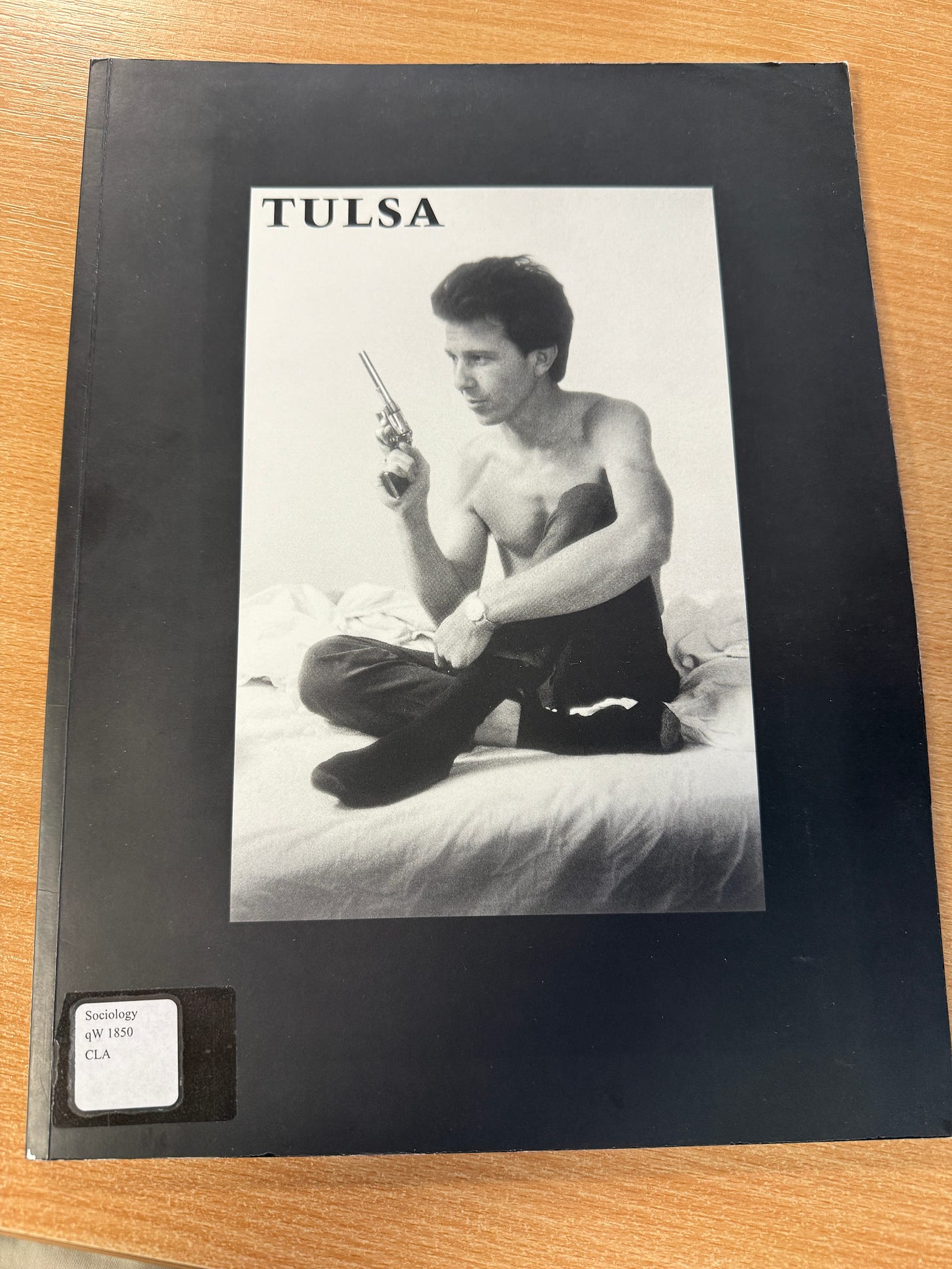

While I don’t have personal experience of drug addiction, I see the consequences every day in Glasgow. I want to help or at the very least understand the problem. For this, I turn to photography and immediately thought of Larry Clark’s classic 1971 photobook, Tulsa, which I found in the sociology section of the library.

When it was first published, Tulsa shocked people by presenting drug taking from the inside. Clark’s mother was a photographer, so it was natural for him to take a camera everywhere. But what is most surprising for modern readers is how much of a morality play it is. Many of his friends had died from drugs, and Clark paired images of people enjoying themselves with those of them suffering. Despite having few captions, the word “dead” appears several times.

It is notable that the drug they took was amphetamines. I assumed, naively perhaps, that when people are injecting it is usually heroin. Having been given morphine in hospital, I know how great it feels to transcend pain and anxiety on opiates. Amphetamines, as well as helping them forget their problems, make people feel superhuman.3

While Tulsa shocked, it is Larry Clark’s second book, Teenage Lust (1983), that now feels more controversial. In it, Clark, as a thirty-year-old man, hung around with teenagers with whom he took drugs, had sex, and documented their lives in intimate, exploitative detail.4 It’s less bleak than Tulsa and captures the fun side of debauchery.

No drug policy that ignores the enjoyable aspect of drugs can ever be effective. While drugs may end up as a form of pain management, they always start with pleasure. Not just chemical pleasure, but pleasure in having a community and connecting with others. Unless a society provides forms of community that help people transcend the ego, its members will always end up seeking it elsewhere.

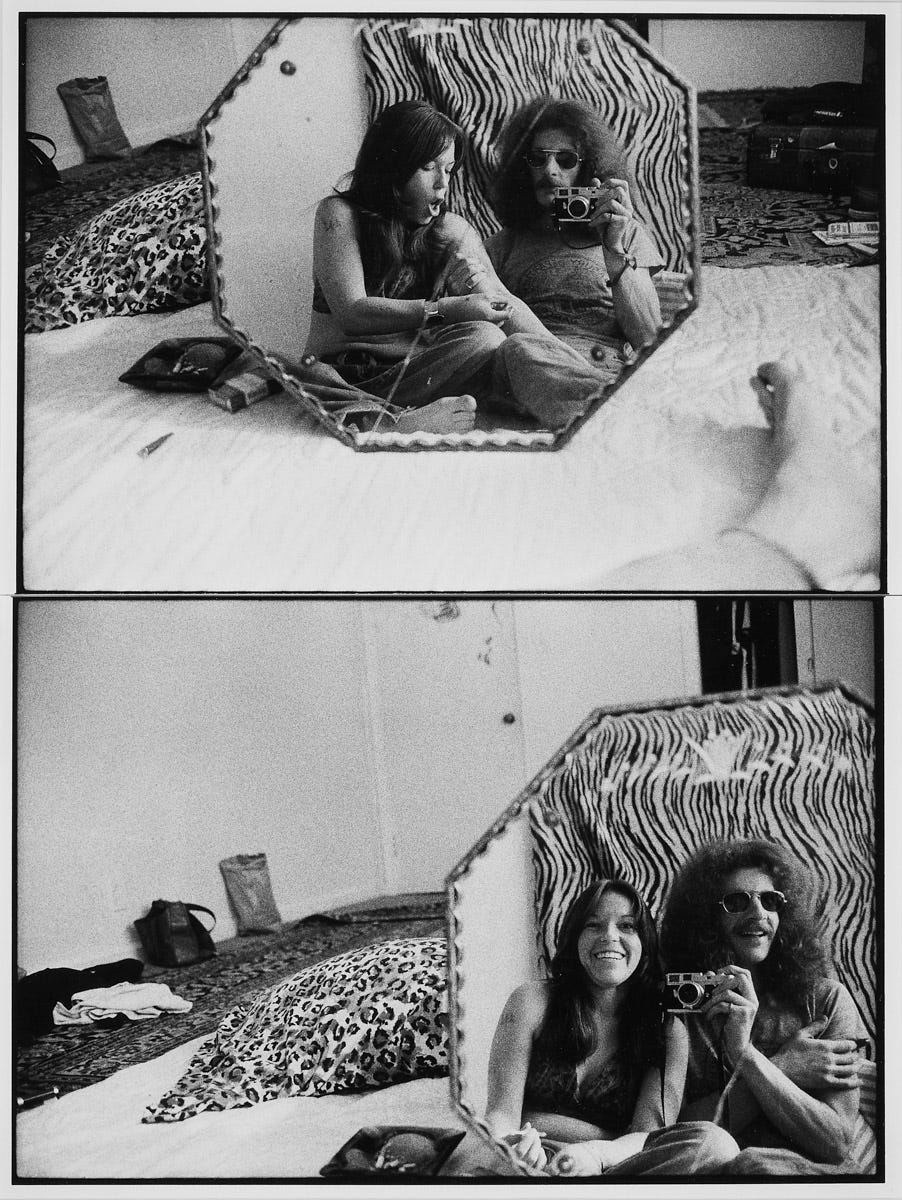

Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986) documents a “chosen family” held together by drugs, sex, and board games. In her 1996 afterword, Goldin writes that “In the beginning, drugs were about expansion; but by the end they became a prison.”5 Actions have consequences, but the consequences of addiction are so far in the future that it seems frivolous to worry about them in the present.

Even when the drugs no longer work for pleasure, they still help form social bonds. I recently met Aidan Mark Wilson, who spent time in Valencia documenting “a small family of characters from the edges of society” who hung out in the home of an “old drinker” called Juan.

In the stillness of Wilson’s portraits, I see the resignation to pain and rejection that is at the heart of being an addict. In Juan’s Place, they found “a modicum of protection and a community without judgment.”

Wilson’s pictures are empathetic and taken without condemnation. They show the consequences of addiction without the glamour of youth. Perhaps this is where photography can help. For it is only by thinking through the consequences of our actions that we can escape the hedonic trap.

Post Script

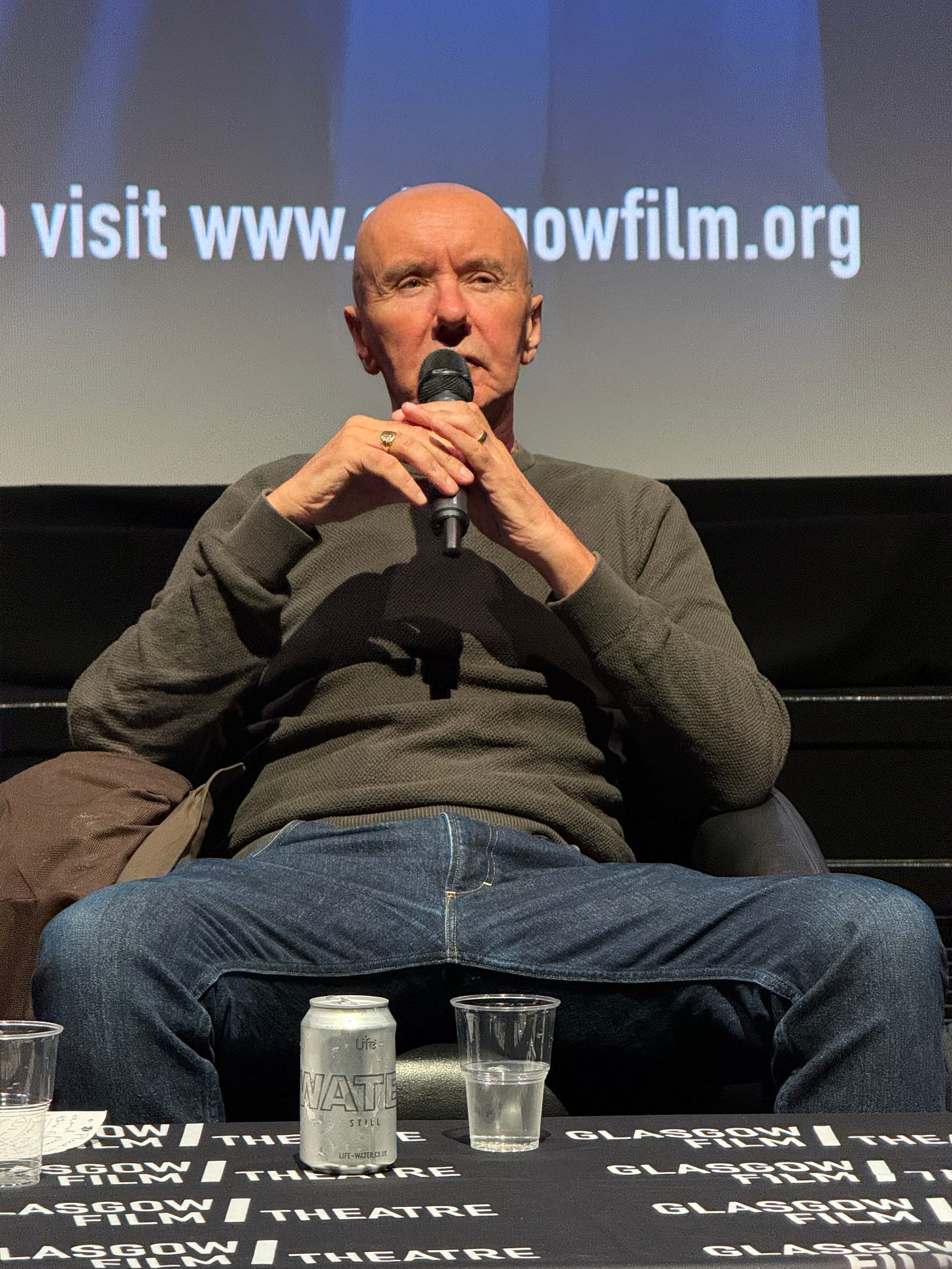

On Wednesday, I saw Irvine Welsh, author of Trainspotting (1993), do a Q&A after a screening of Paul Sng’s new documentary, Reality Is Not Enough. Welsh advocates drugs as a way of escaping drudgery and accessing other realms, while taking a staunch view that persistent usage doesn’t lead to anything good. He revealed that he is no longer an atheist and believes in a cosmic connection between everyone and everything.

The previous day, I saw Turner prize winner, Mark Leckey, talk about how he makes art to induce a sense of transcendence. Like Welsh, Leckey had come of age during the era of Acid House, when ravers achieved states of bliss through dance music and drugs. For both Leckey and Welsh, this experience formed a template for what art should aspire to achieve.

Indeed, in his recent video, Carry Me into The Wilderness, Leckey gets pretty close to an ecstatic religious epiphany. It seems that a new spirituality is struggling to be born. Hopefully, it will reach those who need it most.

Peter Krykant, the man who played a key role in promoting such facilities sadly relapsed and recently died.

Indeed, in low doses, it is used as an ADHD medication to help people focus in the modern world.

Few artists have as much of an idée fixe as Larry Clark. He is obsessed with groups of teenagers. His own family life was unhappy—on Marc Maron’s podcast, he explains that his father didn’t love him, so he sought fulfilment in teenage abandon.

The full paragraph from Nan Goldin is worth quoting:

In the beginning, drugs were about expansion; but by the end they became a prison. Originally, I did drugs to have more vision, to have more clarity, to lose all inhibitions, to be completely spontaneous and wild. For a long time it worked. But it’s hard to sustain that for too many years. When I crossed the line from use to abuse my world became very, very dark—between 1986 and 1988.

Neil, this is a really thoughtful and powerful essay. I appreciate the way you’ve used photography not as voyeurism, but as a lens to try and understand the layered realities of addiction, the pleasure, the community, the pain, the consequences. So often the discourse gets flattened into either glamour or horror, and you’ve shown how both are true at different points, and how important it is to reckon honestly with that.

Your line that “no drug policy that ignores the enjoyable aspect of drugs can ever be effective” is bang on. Those of us in recovery know that the first hit was often about connection, relief, belonging, even joy, and unless policy and culture offer genuine pathways to transcendence, people will keep looking for it in substances. That’s why recovery communities matter, they can be places of meaning, solidarity and even ecstasy, without the collapse that comes later.

I also loved how you read Nan Goldin’s afterword and Aidan Mark Wilson’s portraits the recognition of community without judgement, but also the resignation that creeps in. You captured that tension with compassion. It’s the same tension recovery advocacy has to work in, holding empathy without ever losing sight of the wreckage drugs bring.

Thank you for writing with such honesty and curiosity. Scotland needs more people willing to look at this crisis with clear eyes, cultural sensitivity and moral seriousness. Please keep going your voice adds something vital to the conversation.

I’ve not come across Larry Clark. Great to discover an influential photographer from near my home town. Great read Neil :)