Photo ... therapy?

Mindfulness, Jo Spence, and the use of photography help solve mental health issues.

“I’m stressed.”

“I can’t sleep.”

“I hate myself.”

“I don’t know what to do.”

Such are the kind of statements that we might associate with poor mental health. In each case, there is an ‘I’ that suffers because of the demands placed upon it. The ‘I’ that creates the illusion of being separate from the world.

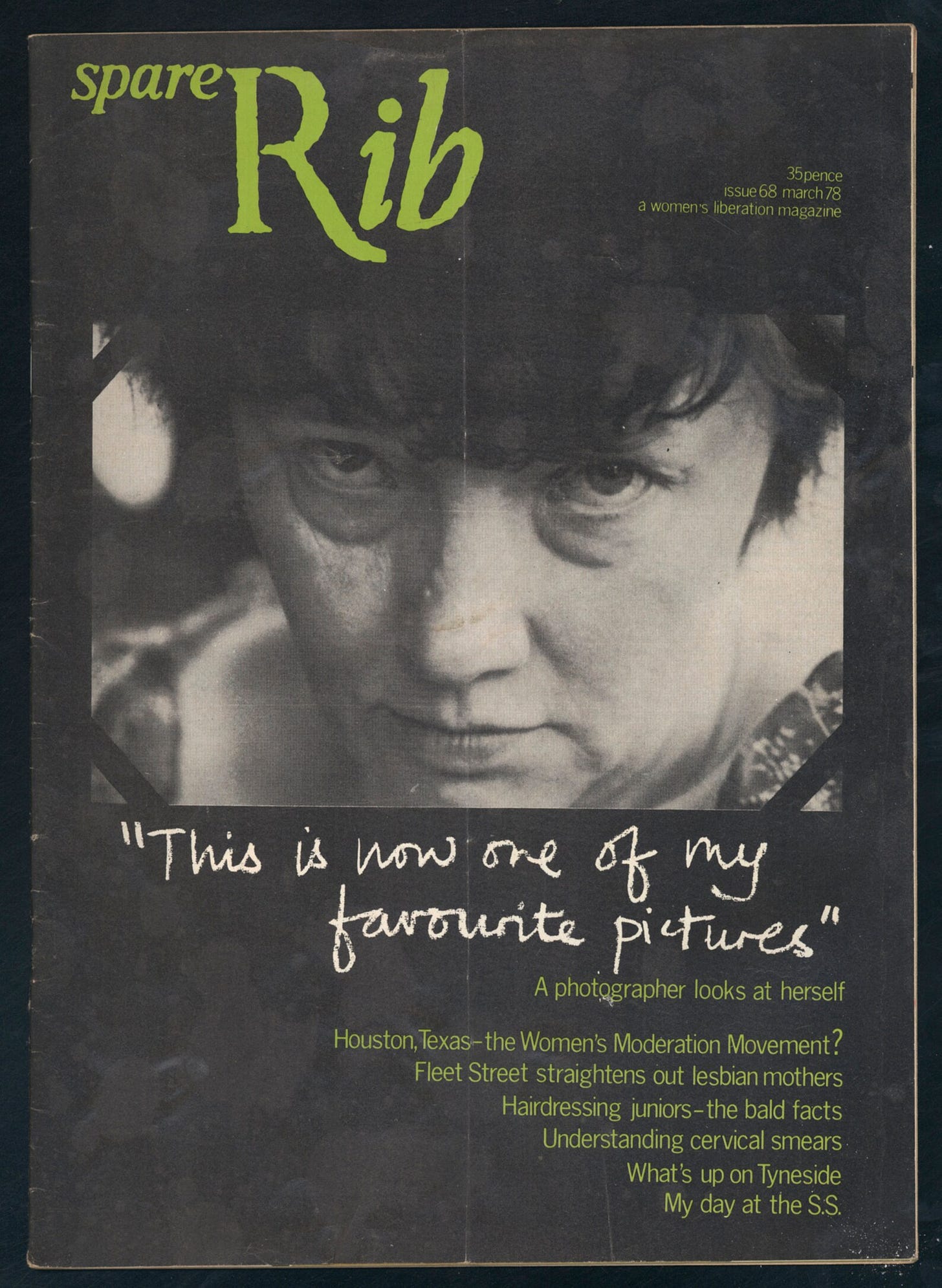

Therapy is the attempt to reconcile that ‘I’ to reality. In Freud’s memorable phrase, psychoanalysis helps turn “hysterical misery into common unhappiness”. Sadly, for Freudians, the default fix for mental health is no longer years of talk therapy but mindfulness.

Photography and Mindfulness

Derived from Buddhist meditation, mindfulness is a catch-all term for a sense of embodied attentiveness. The NHS guide suggests taking notice of “thoughts, feelings, body sensations and the world around you.”

It is easy to see how photography might be used for mindfulness.1 The camera is an externalised ‘I’, and the images we create help us check if our perceptions correspond with reality. Combine that with a long walk, and you have an excellent way of escaping the prison of the mind.

This week, I set an intention to be more mindful in my photography; to stay with my feelings and experience the outside world as it is, rather than listening to music to distract me from my thoughts.

And it worked … sort of. I was relaxed, at least. But is that enough at a time of political turmoil?

One common critique of mindfulness is that it encourages people to quietly accept the injustices of the world rather than fix them. Like anti-depressants and CBT, mindfulness rarely addresses the structural causes of mental health problems.

Jo Spence and Phototherapy

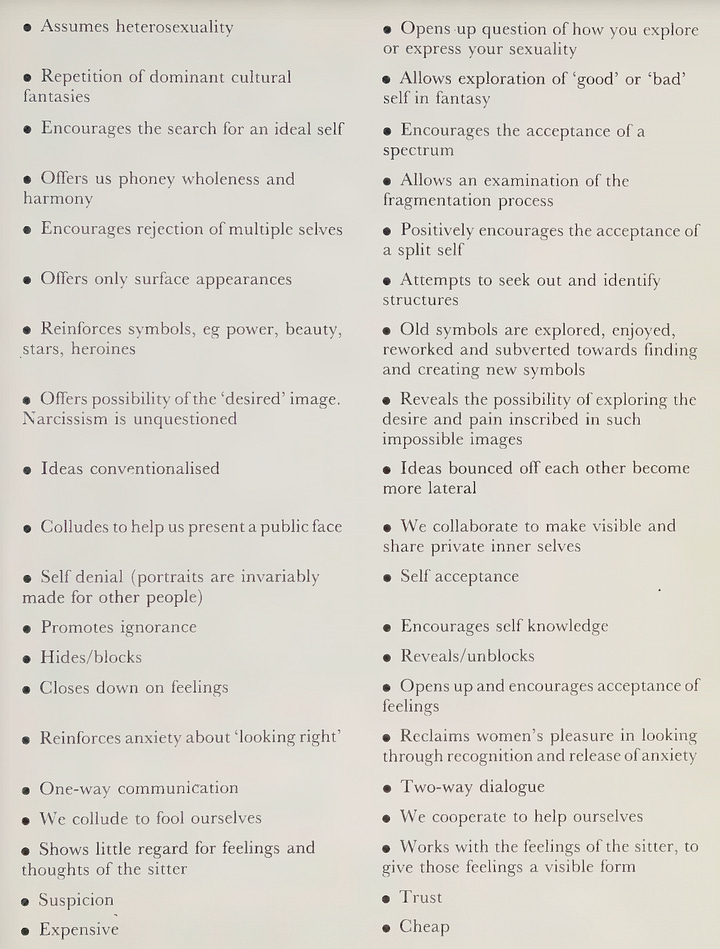

Enter Jo Spence (1934-1992), a photographer and self-described cultural sniper who, along with therapist Rosy Martin, proposed an alternative to psychoanalysis in the form of phototherapy.2

For Spence, it wasn’t enough to be reconciled with the world; the point was to change it. In collaboration with people like Rosy Martin and Terry Dennett, she used Marxism and Psychoanalysis to not just examine the past but to critique the present.

As Malcolm Dickson, who curated an exhibition of her work at Street Level Photoworks, said: “Jo believed that […] photography is a tool that can be used by everyone in any situation for self-knowledge, personal growth and of course social critique.”

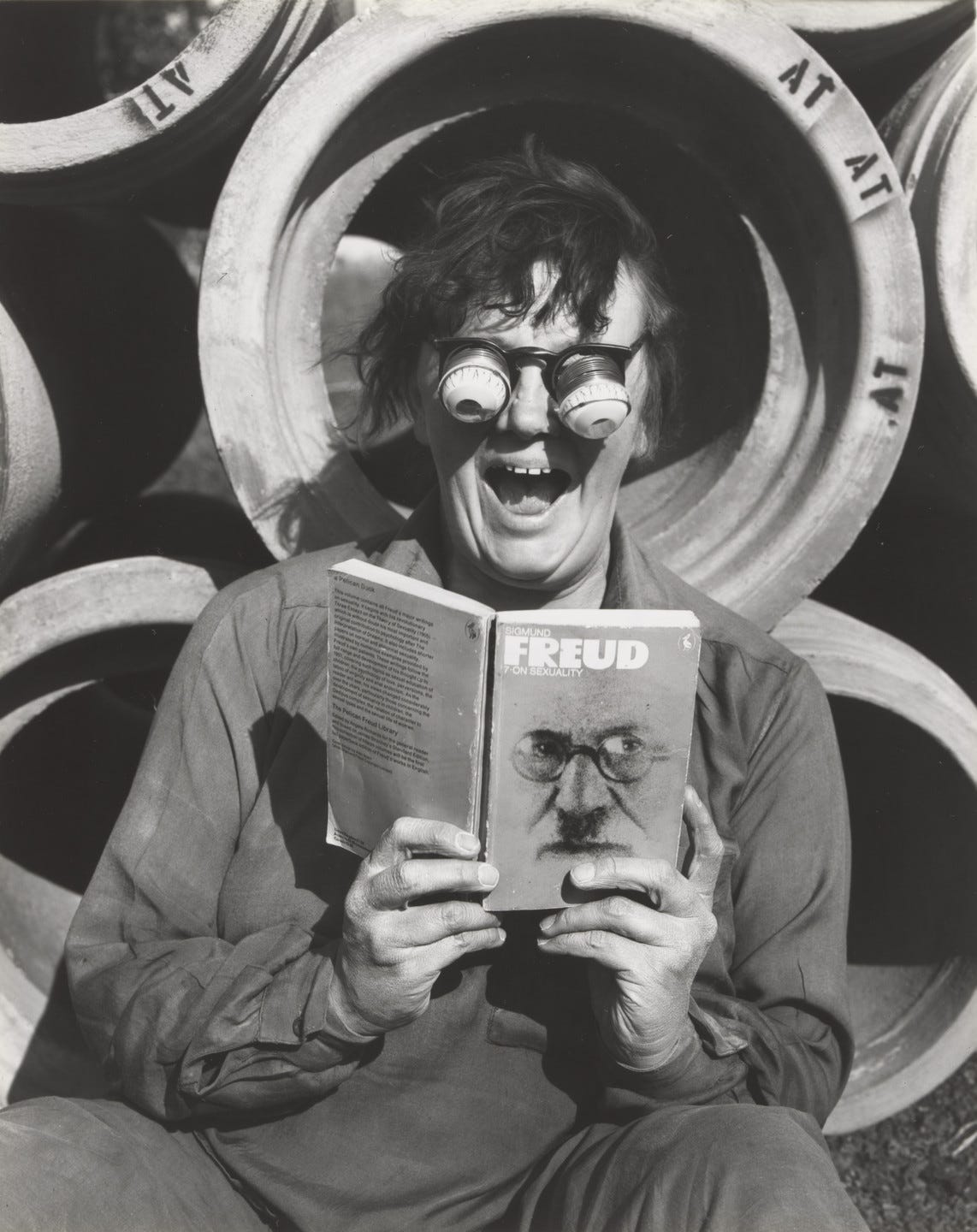

In Spare Rib, Spence joined other radical second-wave feminists in challenging beauty standards, sexual politics, and the insanity of nuclear weapons. Spence learned to deconstruct everything from her upbringing and the fairytales she grew up with to her career as a commercial photographer.

Like John Berger, in Ways of Seeing, Spence saw conventional art history as an expression of patriarchal and capitalist domination. She sought to challenge the imperatives of advertising by showing how dissonant it appears when juxtaposed with normal people.3 In 1984, under these influences, Spence and Martin developed a new psychological cure …

Phototherapy (not to be confused with the light therapy of the same name) attempts to use photography as a tool for both mental health and political consciousness raising.

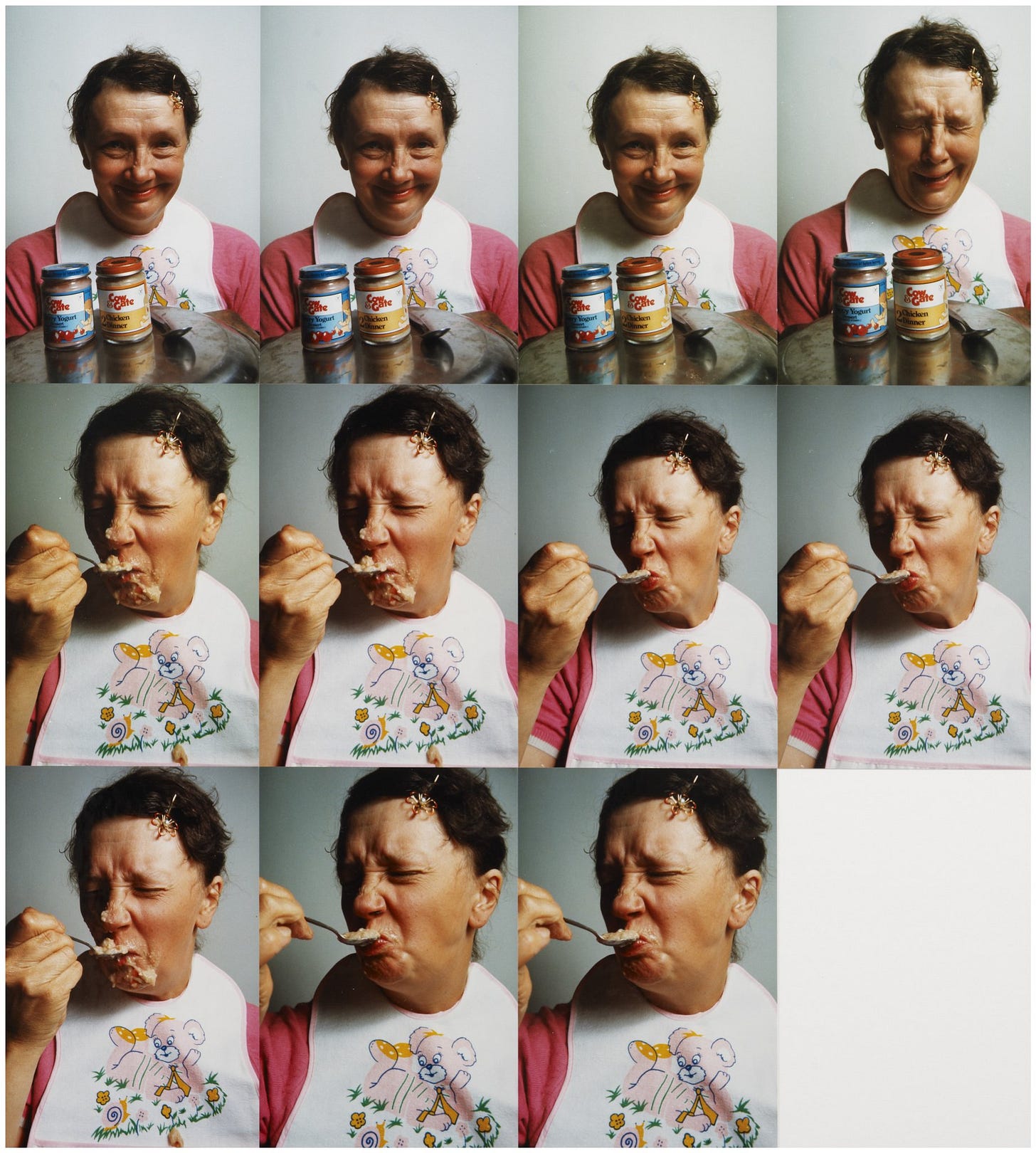

The basic premise is that two people, in collaboration, discuss past traumas and then perform them for the camera. In making the image, there is an opportunity to reframe, objectify and overcome the trauma.

It is extremely cringeworthy to see Jo Spence pretending to be a baby. But cringe is external judgment reflected inward. If we can sit with cringe, perhaps we can sit with trauma.

As Rosy Martin put it in a 1987 interview with the BBC:

“People seem to think, ‘Why on earth should you want to put your private distresses on public display?’ My answer to that is that they’re not just my own personal distresses. A lot of them have much more general ramifications.”

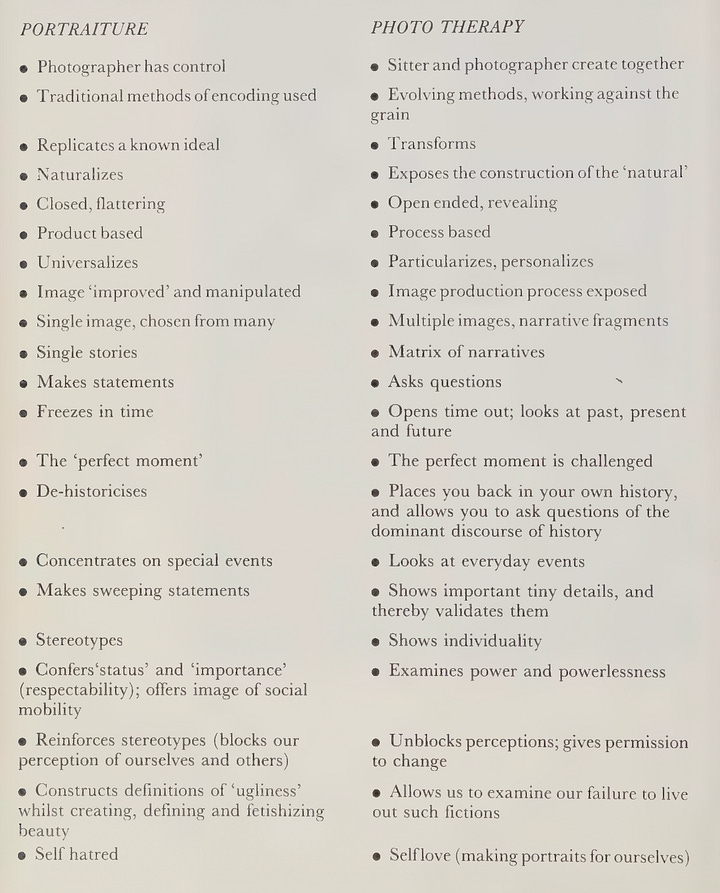

As well as being a tool for mental health, Phototherapy is also a way of rethinking portrait photography. Spence and Martin’s list of differences between the two is worth studying:

While the photos she made aren’t to everyone’s taste—a recent retrospective was titled Beyond the Perfect Image—they are sufficiently different to repay close attention. It is also fascinating to see how she developed as an artist.

Her angrier images from the eighties give way to textured work like The Final Project, made while she was dying of leukaemia. Spence projected double exposures to create oceanic images. It is as if, in reconciling herself to death, she opened herself up to being egoless.

It is a stark reminder that therapy is always a process. Both mindfulness and phototherapy can be part of that process, but never a destination. In a note from January 1992, found after her death, Spence asks that any retrospective of her work finish with her being engaged with the world beyond the self:

Don’t end up with Phototherapy but with the crisis (Public/ Private) work. I would hate to be known as only having worked on Subjectivity and not given a fuck about anyone else.

Hopefully, we can still use her as an inspiration to go beyond mere mindfulness into an engagement with social and psychological well-being. We certainly need it, and we might even find a deeper mindfulness at the end.

A quick search brought up lots of examples: Kim Fuller’s Mindful Photography, Ellie Macdonald’s Capturing Calm, Matthew Bingham’s Soul Photography, Tobias Holzweiler’s Mindful Photography, and Giles Thurston’s Meditative Frame.

I have been thinking about Spence this week after receiving a copy of the new book, Jo Spence: The Unknown Recordings, which transcribes hours of interviews with her.

In a long interview with Val Williams, found in the new book, Spence says:

That was a new word in those days, stereotype. Really grappling with that, we were! Because nobody really knew what it meant. It was slipping about all over the place. We talked about bias, stereotypes and bias, that’s what we kept on saying; and it took years to ask, ‘Biased as opposed to what? What is the real if this is a bias?’

I really appreciate the dive into Jo Spence's work. I didn't know much about her. Also, reading the comment section, I appreciate the comment below by Keith. As someone who is generally interested in mindfulness and art as therapy etc., I also agree with the assessment that this mental health epidemic has a lot to do with how much time we have to focus on ourselves. There are other factors, of course, and mental health struggles and conditions are still real, but there is a lot of truth in this thoughts. Anyways, this is giving me a lot to think about it. I am also interested and curious in the book you mentioned.

Excellent read, Neil! I wasn‘t familiar with her or her work, but will take a deeper look as I am a big believer that photography had therapeutic values. Thank you for writing about this.